HOW IS THIS DICTIONARY DIFFERENT?

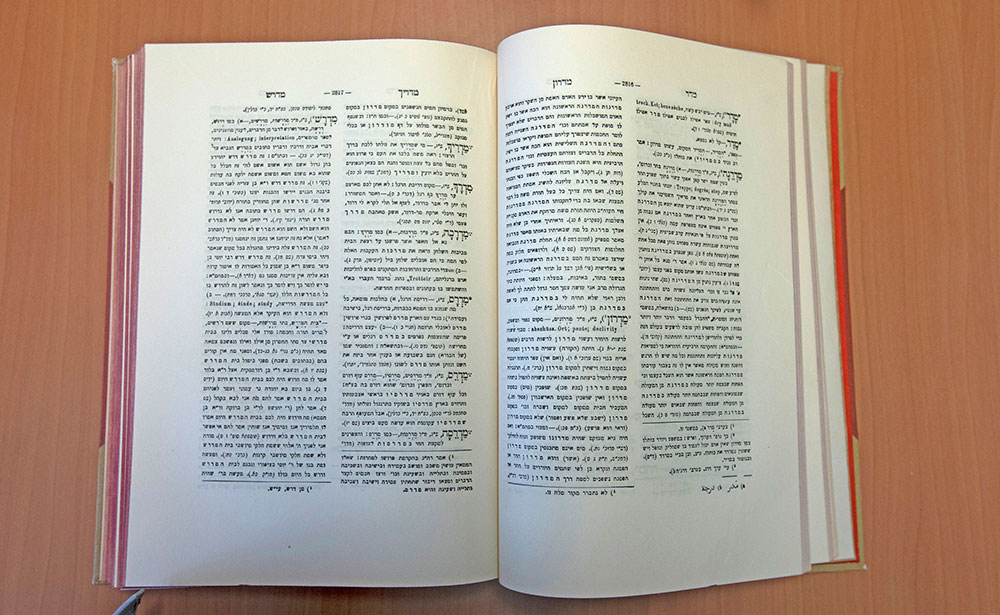

Original Ben Yehuda dictionary. Showing is Volume MEM (M)

Ben Yehuda spent most of his life searching for ancient Hebrew words that had been lost. He also sought to find the origin of words and examples of their usage, as well as their changes in meaning throughout the centuries. He scoured libraries all over Europe and the Middle East. And when he moved to the United States during World War I to escape Turkish persecution, he spent four years searching the great libraries of the United States.

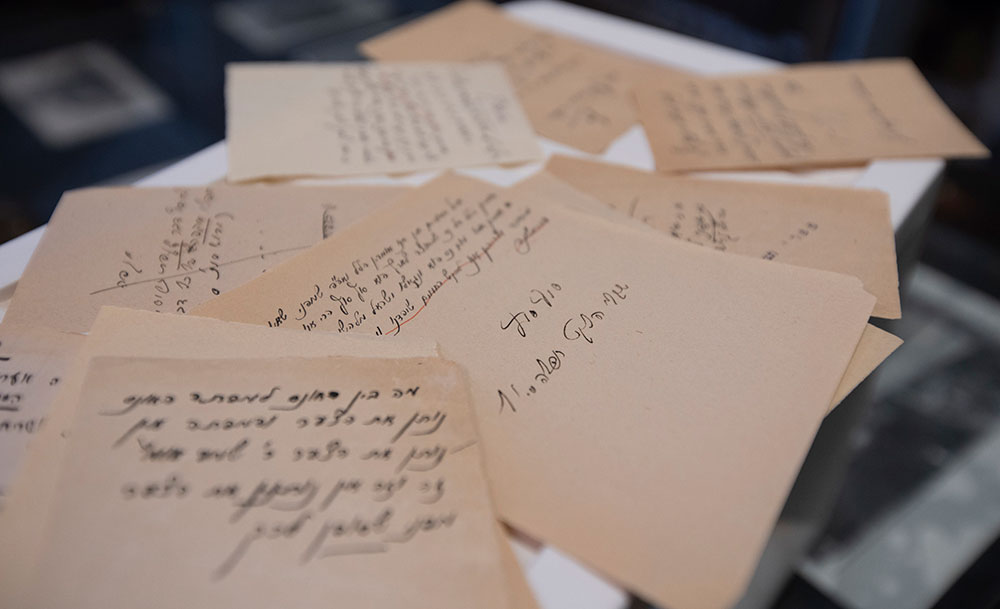

When he fled Palestine in 1914, he had already accumulated about 450,000 notes concerning sources for Hebrew words. His wife, Hemda, packed them up and turned them over to the American consulate in Jerusalem for safe-keeping. Those notes were taken from over 40,000 books he had consulted that had been written over a period of more than two thousand years.

Those who thought that his dictionary was going to be a mere list of Hebrew words with brief definitions were in for a great surprise. This was to be unlike any dictionary ever compiled. His goal was no less than an encyclopedia of the Hebrew language. He identified the origin of each word and provided its sister words in other Semitic languages. He provided synonyms and antonyms. He traced the changes in the meaning of the word through the centuries. And he provided overwhelming examples of the use of the word in sentences to help the reader see how to use the word in conversations.

A WORK OF MULTI-LANGUAGES

After each Hebrew word would come the translation into French, German and English. This made the work unique; a multilingual dictionary in Arabic, Assyrian, Aramaic, Greek and Latin.

Moreover, it was a thesaurus as well as a book of definitions. After each word, Ben Yehuda listed all the other words which were in any way connected. The reader was given the origin of each word, an explanation of its construction, a comparison with its sister words in other Semitic languages, the changes it had undergone down through the ages, and all its nuances, shades, forms, inflections and uses.

After each word were examples of its usage, which Ben Yehuda called “witnesses” or “proofs.” With a language as old as Hebrew there were bound to be many more shadings and colorations of meaning, and even conflicting uses of a word.

He dug out and listed 335 different ways in which it was possible to use the Hebrew word lo, meaning “no” or “not.” There were 210 “witnesses” for ken (yes).

“WITNESSES” FROM EVERYWHERE

Many of his “witnesses” were quotations from the Bible and other religious books, but there were often long passages from secular literature, from the works of little-known poets, or from manuscripts he had found somewhere in a distant library. These quotations were interesting reading in themselves. They gave pictures of the life of early Jews in their homes, market places, fields and ghettos.

The little marks which Ben Yehuda sprinkled through his manuscript were marks of his honesty. These symbols appeared alongside words which he himself had created. “I put them in so the reader can see immediately that these are new words, and if he does not like them he should consider them as non-existent.”

He was the first to make a regular and systematic practice of coining Hebrew words to meet the practical demands constantly being made of the language in daily speech, journalism, science and literature.

In his later years, he co-founded and established the ruling principles for the the Language Council. The Council gave way to the Academy of the Hebrew Language, which adopted Ben Yehuda’s rules and took upon itself his life’s work. The Academy, still housed at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, approves new Hebrew words to meet the ever-evolving needs of contemporary Israeli society.

Theodore Herzl, considered the Father of modern Israel, had a famous saying still quoted by Israel’s school children today: “If you will it, it is no dream.” But Ben Yehuda simply said, “It is not a dream, period.”

Example of the 500,000 notations of word sources Ben Yehuda catalogued in creating his Hebrew dictionary. Seven volumes were completed before his death. All volumes were completed from 1908 to 1959.